If Walls Could Talk

A new book explores the extraordinary links between a Victoria hotel and British espionage. For its author it’s a tale that still remains close to home. By Jonathan Whiley

Tucked into an unassuming corner table at Victoria’s St Ermin’s Hotel, dressed smartly in a classic black suit complete with a crisp white shirt, sits a man many could regard as a spy.

As I approach he shoots me a kindly smile, shakes my hand firmly and produces a sleek black leather briefcase.

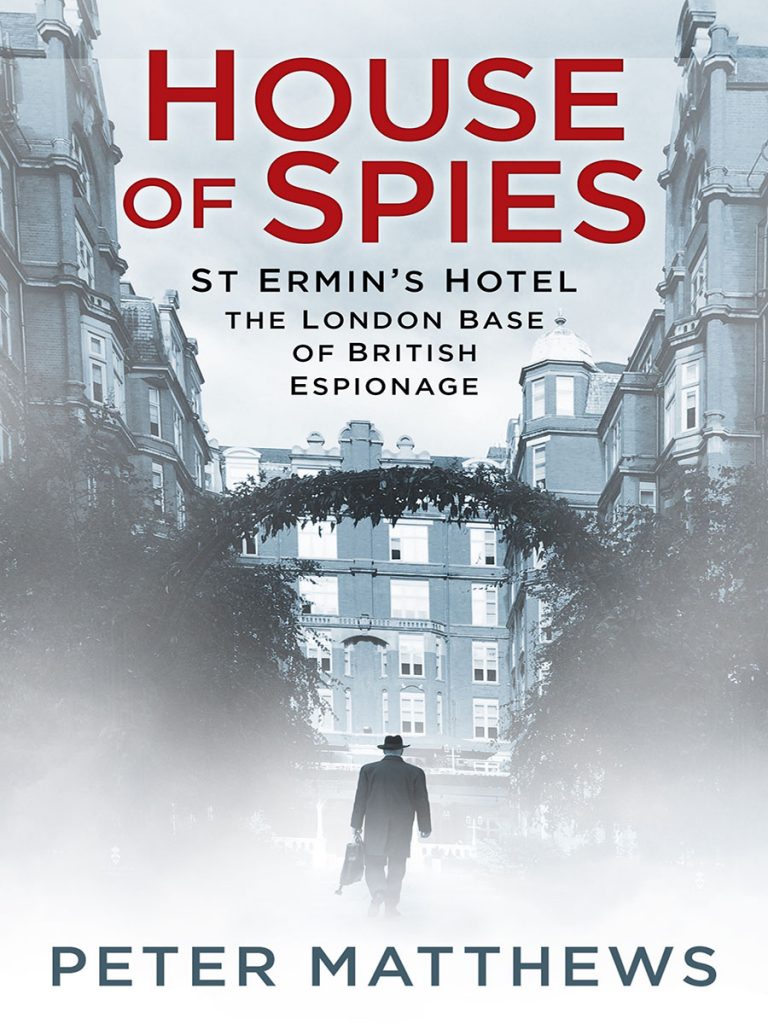

He unlocks it carefully and places a sizeable document on the table. The pages tumble towards me – House of Spies, by Peter Matthews.

The deep-set eyes on the other side of the table belong to the manuscript’s 86-year-old author, a former intelligence officer, who has spent the last 18 months piecing together a book that could pass as the script of a Hollywood thriller.

Except, of course, it’s entirely based on real life. His life. The lives of secret service agents, MI5 and MI6 officers and countless other intelligence personnel whose espionage work had a significant impact far beyond some corner of a foreign field.

“This was the work canteen of MI5,” says Peter, glancing around the hotel’s Caxton Grill restaurant. “They came here to lunch, to drink, they took rooms to interrogate people, they took rooms to make plans.”

The only publicly accessible establishment in London closely associated with the history of British espionage, during the 1930s St Ermin’s was used by the Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6 as it’s otherwise known.

In 1940, Sir Winston Churchill – who enjoyed a glass of his favourite champagne in the bar – formed the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a group he vowed would “set Europe ablaze”.

“Although there wasn’t a great deal of mayhem taking place in this building, it caused a lot of mayhem elsewhere,” says Peter.

The SOE was a secret organisation set up in July 1940 to help resistance movements and carry out espionage plots in enemy territory.

Within striking distance of the London branch of the Government Communications HQ on Palmer Street, Secret Intelligence Service offices in Artillery Mansions on Victoria Street, MI9 on Caxton Street and the MI8 listening post on the roof of the passport office in Petty France, they took over the entire top two floors of the hotel.

Among the notable names to pass through its doors include James Bond author Ian Fleming and double agents Kim Philby and Guy Burgess, members of the notorious Cambridge Five spy ring.

“Philby was first, he was recruited here,” says Peter. “Then Burgess came. They created a large working part of SOE. As I say in the book, the Cambridge spies did this country no good in the Cold War but helped hugely in the development of the SOE.

“Burgess started SOE schools here and there were about 150 of those around the country. One of the schools trained the assassins who went to Czechoslovakia and killed [Nazi Reinhard] Heydrich.”

Peter recalls his own life story. In his younger days he worked for civil engineering company Pauling & Co who made Mulberry harbours – portable structures developed during the Second World War that proved crucial in offloading cargo on to the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

“I’ve known the bar here since I was 20,” says Peter with a raised smile.

“The various people who built the Mulberry harbours used to come here and we had uproarious times. Then that was all spoilt because I went in to the army in 1947.”

Soon after joining, Peter was flown to the German capital on the first flight of the Berlin Airlift, which saw food supplies delivered to combat the Soviet Union blockade.

“That was a very big event in my life,” he reflects. “Berlin, at that time, was full of spies and I got to be one of them.”

He qualifies this revelation by stating that it was “intelligence gathering at a very low level”.

“We were concerned with something called TICOM, which was the Target Intelligence Committee,” he adds. “We were stealing the technology the Germans had in developing the coding machines, coding technology, and taking it all back to Bletchley Park and GCHQ.”

What was it like to be in a city surrounded by such turmoil? “Unbelievable,” he says, pausing. “They were still pulling dead bodies out of the water supply. Women used to stand in the food queues discussing how many times that week they had been raped by Russian soldiers.

“It was a time when we were doing lots of security things with the Americans. As a side issue I was guarding Spandau Prison where [Rudolf] Hess and [Erich] Raeder and the seven Nazi criminals were.”

Peter says that he was tasked with trying to find out what the Red Army and the Stasi [East Germany’s secret police] were planning.

“It was a terrifying time if I think about it now but it was exciting too,” he says.

“One of the things I used to do was to go round to the dance halls and make a note of the cap badges of all the Russian soldiers.” He pauses and chuckles. “I got some really good intelligence there; I got all the first names of all the girls.”

Fluent in German and immersed within the intelligence group of the former Wehrmacht [the Nazi armed forces], Peter was able to introduce people to the Americans and in turn, under an unofficial agreement, reported to the British services about what Uncle Sam’s forces were up to.

“What the Americans were doing was as important to the Brits as what the Russians were doing,” he says.

After three years, he left the army and returned to Victoria, where he met a member of MI6 working in Artillery Mansions and was recruited for a department he refers to as “the dodgy documents division”. Sharing the same offices was one George Blake, who would go on to become one of the conflict’s most notorious double agents.

Peter has previously written a book on signals intelligence, but this is new book is different; more autobiographical, inspired by family and a conversation, bizarrely, with comedian Ken Dodd.

“I have a couple of grandchildren and I wanted to tell them what I’d done,” he says. “The thing that made up my mind on this was Ken Dodd.

“He is quite close to a friend of mine and he said, ‘You need to reinvent yourself every 10 years.’ I thought that was quite profound. I tried a number of things – including beekeeping – and I finally came up with writing a book.”

Except, given his background as an intelligence officer, it wasn’t that simple.

“You never retire from intelligence,” says Peter, who became a journalist in later life and is a trustee and archivist for the Foreign Press Association based in Victoria. “Wherever you go they’ve got tabs on you. They use you when they want to.

“When you’re writing a book on security your researchers are noted [by MI5] and they evaluate whether you’re a danger or not.”

I joke that perhaps we’re being watched at this very moment with intelligence services still making use of the hotel. Peter, unnervingly, doesn’t dismiss it entirely.

“The SOE came to a sudden end in 1945 but MI6 continued here until the 1960s,” he says. “I was here three weeks ago and there was Frederick Forsyth [who revealed in his own autobiography that he worked as a spy for MI6].”

As we leave, Peter stops in the lobby to point out a secret passage in the middle of the grand staircase. I hadn’t given the unassuming door a second glance. But then that’s the thing with the world of espionage, isn’t it? Everything’s not quite what it seems.

House of Spies, by Peter Matthews, published by The History Press, is out on October 19. To request a signed copy at no extra cost, email peter.matthews23@btinternet.com.