Chelsea’s Literary Links

As a place of pilgrimage for literature lovers, few areas of London can rival Chelsea. Debbie Ward takes a tour of its most literary locations.

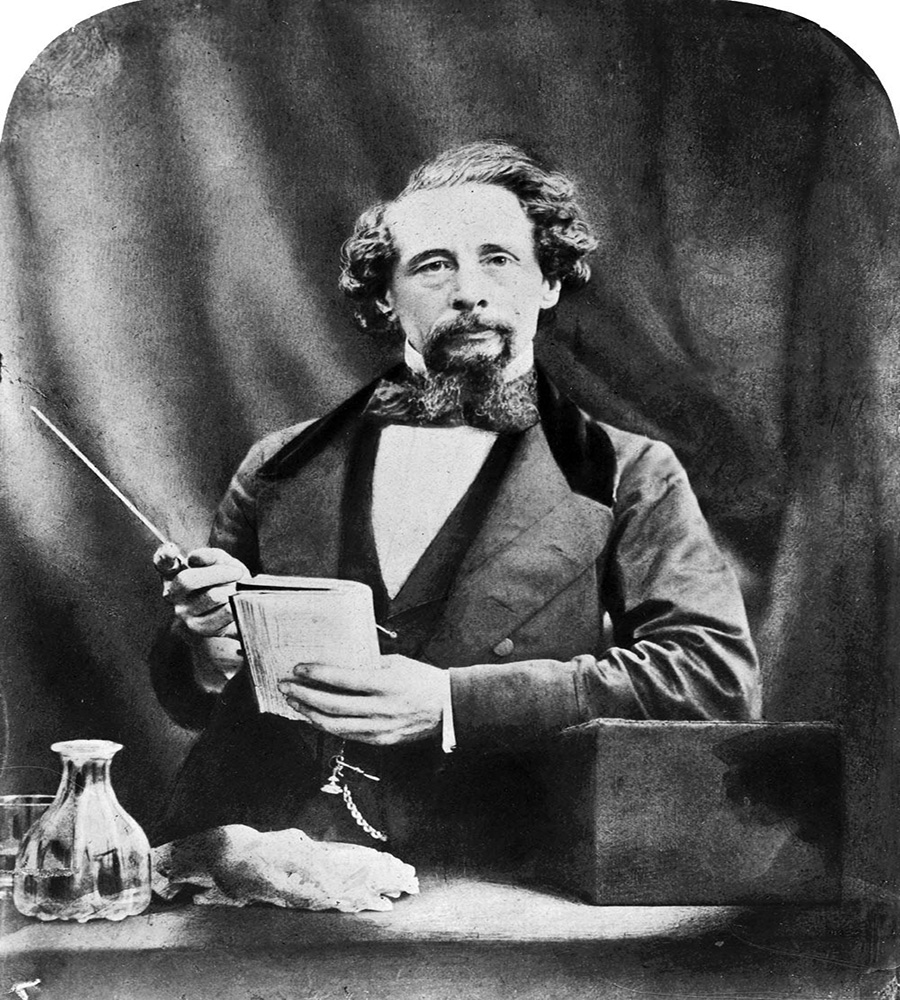

“Few would venture to Chelsea, unarmed and unattended,” Charles Dickens famously wrote in his 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge, when the area was known for highwaymen. Of course a bad reputation meant reasonable rents, which, coupled with a Bohemian feel, began attracting braver writers in their droves.

Historian and social commentator Thomas Carlyle shared Dickens’ inauspicious view, telling his brother this ‘literary classical ground’ was nevertheless ‘unfashionable’ and ‘unhealthy.’ He lived in a Cheyne Row house now preserved by the National Trust where you can still see his attic study. Dickens, Mrs Gaskell and Tennyson were among friends. In fact, Dickens also braved Chelsea’s mean streets to marry locally, at St Luke’s Church.

Nowadays the art-minded may browse the Saatchi Gallery or buy books on artists in Duke of York Square’s stylish Taschen bookstore. Back in the 19th century, they gathered at 16 Cheyne Walk, home of Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti, an artist, translator, poet and eccentric who filled his garden with exotic animals including an armadillo, a peacock and wombats he described as ‘a joy, a triumph, a delight, a madness.’ One wombat is immortalised in a William Bell Scott sketch on 16 Cheyne Walk notepaper now held by The Tate.

Famous bear Winnie the Pooh later resided at 13 Mallord Street, where A.A. Milne lived from 1919 until 1942 and wrote his most famous works. Milne’s son, the real Christopher Robin, grew up here with his teddy and his sister Alice with whom, as the poem goes, he would walk to see the changing of the guards. In his adult years he worked a while at Peter Jones.

Another bear fan was John Betjeman who even as an adult chatted to his well-loved teddy Archie on tube journeys from Sloane Square, so inspiring Evelyn Waugh to create Sebastian’s relationship with his bear in Brideshead Revisited.

Betjeman’s childhood home on the ‘slummy end’ of Old Church Street features in his autobiographical poem Summoned by Bells. He also wrote Holy Trinity, Sloane Street in honour of the magnificent church he called ‘the cathedral of the Arts and Crafts movement’ which he helped save from closure in the 1970s.

In the early 19th century Jane Austen stayed in Sloane Street with her brother Henry who helped her publish Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. She later visited his Hans Place home, breaking from writing to visit the much admired and still existing garden to ‘refresh myself every now and then.’

Austen also stayed at the Cadogan Hotel in 1795, where, exactly a century later, Oscar Wilde was arrested for ‘gross indecency with other male persons’. The saga was immortalised in Betjeman’s The Arrest of Oscar Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel in which a policeman tells Wilde: ‘“We must ask yew tew leave with us quoietly For this is the Cadogan Hotel.”’

Wilde wrote his most famous works at 34 Tite Street. Despite nearly being erased due to his notoriety, he remains among local literary figures depicted in a mural at Chelsea Old Town Hall, a building now licenced for same-sex weddings.

Wilde was publically shamed in Chelsea but Dracula author Bram Stoker became a hero during his time at 27 Cheyne Walk when he dived into the Thames to rescue a drowning man. The man died but Stoker was awarded a Royal Humane Society medal.

Stoker’s famous Gothic novel is part set elsewhere in London but the King’s Road does have a more ignominious appearance in Hammer Horror film sequel Dracula AD 1972.

In the 1940s, Dylan Thomas mocked Chelsea’s more fashionably addressed, calling them the ‘Cheyne Gang’, himself occupying a leaky bedsit in Manresa Road with a stack of classic novels for a table. He also lived, he told his brother, ‘amid poems, butter eggs and mashed potatoes’ on Redcliffe Street.

An infamous drunk, Dylan frequented many local pubs, including the Kings’ Head and Eight Bells (now Cheyne Walk Brasserie) from where he was ejected for picking fights with servicemen. In Chelsea (in Dylan’s Footsteps) his daughter Aeronwy, describes how her parents left her in her cot and ‘valiantly ignored the falling bombs’ to go drinking.

Around the same time Laurie Lee frequented the Queen’s Elm and lived in Markham Square, Elm Park Gardens and later novelist Edna O’Brien’s former home in Carlyle Square. His reminiscences of wartime Chelsea appear in A Village Christmas: And Other Notes On The English Year, published posthumously last year. Chelsea was, he says, ‘seedy, calm and semi‑rustic’ and once so deserted he ‘stood in the middle of the King’s Road and shot an arrow from the Markham Arms to the old Town Hall.’

Carlyle Mansions on Cheyne Walk, has been nicknamed Writers’ Block, having housed George Elliot, Somerset Maugham, Henry James and later Ian Fleming, who drafted James Bond’s debut in Casino Royale here. Miss Moneypenny was probably inspired by The Boltons resident Lady Ridsdale, who worked with Fleming at the Admiralty. She once helped dupe the Nazis with a British corpse furnished with false invasion documents. James Bond’s ‘comfortable ground floor flat off King’s Road’ is rumoured to be in Wellington Square, while another fictional spy, John Le Carre’s George Smiley, resides firmly at Bywater Street.

Chelsea has also been the setting for literary romance. In Henry James’ The Wings of The Dove Kate Croy first meets Morton Densher on a tube leaving Sloane Square, while in E.M. Forster’s Howards End Margaret Schlegel re-meets Henry Wilcox on Chelsea Embankment. Even back in 1910 Forster noted the area’s Bohemian quality referring to ‘long-haired Chelsea’.

The borough has also been important for political writing. So-called ‘Angry Young Men’ John Osborne, Kingsley Amis and Harold Pinter debuted their plays at the Royal Court Theatre, which actually coined the ‘angry young man’ tag when Osborne’s Look back in Anger opened there.

Nowadays politically slanted writing continues with local Jonathon Coe, best known for his acclaimed satire What A Carve Up! You’ll find a dig at Chelsea’s grand basement extensions in his latest novel Number 11 in which, he’s admitted, Tregunter Road masquerades as Turngreet Street.

If you want to further immerse yourself in literary Chelsea, hunt down some of the many blue plaques, or perhaps read the novels of Anita Brookner, who died earlier this year. Her characters often wander Chelsea’s streets, visit its mansion blocks and shop in Peter Jones.

And if you’re tracking down the works of Chelsea’s novelists you should visit John Sandoe Books in Blacklands Terrace, which stocks some 28,000 titles. Like Chelsea itself, it had humbler beginnings; it opened back in 1957 with planks resting on bricks for shelves.